Fort Worth Prairie Park

Saving One of the Rarest Ecosystems in North America and Creating the Largest Public Prairie Park in North Texas

The Fort Worth Prairie Park is older than the birth of civilization itself, yet fresh and alive as if born this morning. With your help, we will save what’s left for all future life.

This biodiverse land is a living remnant of 10,000 year old native Fort Worth Prairie, has never been plowed, and is of exceptional quality. It will benefit from some clearing of brush overgrowth and, in a few places, invasive species removal to return it to its highest quality native Texas prairie wildlife habitat.

Fort Worth Report

Photos from Restoration Not Incarceration™ & Fort Worth Prairie Park work week April 2021

Green Source DFW

Green Source DFW, an award-winning digital publication covering environmental news in North Texas, recently published Fort Worth Prairie Park efforts move ahead despite setbacks.

Fort Worth Star-Telegram

The Fort Worth Star-Telegram recently ran this front-page article: "Fort Worth moves forward with land conservation plans" and this op-ed by Jarid Manos: "Fort Worth is losing its natural prairie land. Here's how we can protect it."

Download the Fort Worth Prairie Park Photo Tour and Fact Sheet

Fort Worth Prairie Park & Rock Creek/Lake Benbrook Complex

A Regional Grassland Park for all of North Texas

A National Epicenter for Ecological Health

Once completed, the Prairie Park will be a springboard for prairie restoration and Ecological Health across the Great Plains and the country.

Location: Southwest Fort Worth

Current size: Over 3,000 acres of 10,000 year old, old-growth Fort Worth Prairie on the backdoor of 7.5 million people

Goal: Expand and save as much nearby or adjacent native Fort Worth Prairie as possible before development takes over. This is the last stronghold of native Fort Worth Prairie, a unique ecosystem that was once 1.3 million acres, and is now one of the rarest ecosystems in North America.

“I was born on the prairie, where the wind blew free and there was nothing to break the light of the Sun… and where everything drew a free breath.”

~ Parra Wa-Samen (Ten Bears) of the Yamaparika Comanches, Treaty Speech of 1872

“Sooner or later, I want to be able to tell people that I helped make it better for the buffalo,”

~ Michael, a 15-year-old urban Fort Worth youth and longtime Great Plains Restoration Council Plains Youth InterACTION™ participant

Some photos by Charles Morris

The Fort Worth Prairie Park is older than the birth of civilization itself, yet fresh and alive as if born this morning. Our human ancestors grew up nourished by the fruits and beauty of this land. With your help, we will save what’s left for all future life.

Preservation • Teaching • Healing • Capital Campaign • Facts

1. PRESERVATION

Preservation Vision

- The Fort Worth Prairie Park (FWPP) is a “Where the West Begins” cultural gateway for the growing prairie/plains restoration movement across the Great Plains. It is rooted in the Buffalo Commons thesis, which was famously proposed by Dr.’s Frank and Deborah Popper in 1987 to stimulate a rebirth of the Great Plains by finding new ways for people to live with and alongside the land and each other.

- The FWPP is a wild prairie in southwestern DFW on the backdoor of nearly 8 million Metroplex residents. Easily accessible, it highlights and preserves a remnant of the beauty and wildness of original North Texas prairie, while allowing people a respite from their daily routine by experiencing nature without having to travel to Colorado or New Mexico as many are accustomed.

Preservation Goals

- Preserve one of the largest remaining tracts of native tallgrass prairie in North Texas and further establish the FWPP as a leading national epicenter of Ecological Health, where people take care of their own health through taking care of the living Earth. The once 1.3 million acre Fort Worth Prairie ecosystem is a southern sub-region of the tallgrass prairie, which is the most endangered major ecosystem in North America. The FWPP is even more unique because it blends East with West prairie ecosystems. On the FWPP, lush stands of big and little bluestem tallgrass prairie reach to the sky, shortgrass prairie barrens hearken a broad diversity of Western plant and animal life, and streams, seeps, prairie limestone outcroppings, riparian corridor forest, and pocket wetlands all combine inside a remnant wild prairie of exceptional abundance that offers visitors an experience few people alive have had.

- Expand and connect the FWPP via ecological corridors to additional preservation lands, including the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers public wildlands along Rock Creek (Rock Creek Park) and the eastern shore of Lake Benbrook.

- Build a Visitor Center and Ecological Health Field Institute that offers:

- Extensive opportunities for the general public to get outside and advance land and water conservation coupled to renewed health of people and nature (Your Health OutdoorsTM)

- 21st century education programming for grade-school and university students utilizing ecology to support all areas of learning, (Plains Youth InterACTIONTM)

- Work Scholarships and transitional training for formerly incarcerated young adults, (Restoration Not Incarceration™)

- Eco-therapy for struggling or injured people, including U.S. Armed Forces “Wounded Warrior” veterans from Iraq and Afghanistan

- Interdisciplinary learning within the local-to-global context regarding grasslands and their endangerment worldwide

- An Ecological Health model for people in other eco-regions across the country.

- An informational and interdisciplinary portal to landscape-scale prairie restoration and conservation projects in the United States.

Globally-imperiled status of the original Fort Worth Prairie and its Inhabitants

Much of the FWPP site contains the iconic anchors of the original Fort Worth Prairie ecosystem. Theser are little bluestem, yellow Indiangrass, big bluestem, and prairie bishop (schizahyrium scoparium, sorghastrum nutans, andropogon gerardii, bifora americana vertisol). The FWPP is a G1/G2 plant community according to the Heritage Ranking System, which means globally imperiled with only 6-20 known occurrences remaining.

The FWPP holds international ecological significance as an important breeding and resting ground in the spring and fall for the North American Monarch Butterfly Migration. Hundreds of monarchs have been seen breeding and laying eggs in the prairie in the Spring, and resting in the “Monarch Cathedral” down by Rock Creek in the Fall. Monarch butterflies were named one of the 7 American species most threatened by climate change (Huffington Post, June 2009). In 2012, the number

of monarch butterflies that completed the annual migration from Canada to their winter home in Mexico sank 59% to its lowest level in at least two decades, due mostly to extreme weather, changed farming practices in North America, and Mexican government policies (NY Times, March 13, 2013). Preserving their Spring and Fall breeding grounds and way stations is imperative (ScienceLine, October 2006).

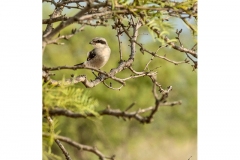

The FWPP is also a Central Flyway grassland for nesting birds whose populations are rapidly declining from loss of habitat. In 2007, Audubon released a national list of once common birds in precipitous decline. Eight of these top twenty declining “once common” birds have been seen on the FWPP. Audubon’s national ranking, which includes bird name and percentage of decline (#1=greatest decline), is as follows:

#1 Northern Bobwhite, 82%

#6 Eastern Meadowlark, 72%

#8 Loggerhead Shrike, 71%

#9 Field Sparrow, 68%

#10 Grasshopper Sparrow, 65%

#13 Lark Sparrow, 63%

#16 Rufous Hummingbird, 58%

#17 Whip-poor-will, 57%

Issues, Challenges and Opportunities

- Protect or reintroduce extirpated and/or threatened and endangered species. Future introduction of the Texas horned lizards is being considered to buttress native biodiversity.

- Conduct research to help thwart localized or global biodiversity decline. The FWPP provides habitat for many declining wildlife species.

- Protect native plant and animal species through ecological landscape integrity, including rare Texas native mussels that live in Rock Creek.

- Insuring ecosystem connectivity from prairie to riparian gallery forest (Rock Creek/tributary to Clear Fork of the Trinity River) to allow wildlife and plants room to survive, as well as genetic interchange.

- Preserve ecological communities and relationships.

- Test, research, and prepare climate change resilience actions. All over the world, people are looking for ways to make ecosystems better prepared for coming climate disruptions. Undisturbed American prairies are particularly suited to withstand climate change, while also offering learning and adaptation strategies as time progresses.

- Some restoration will need to occur:

- Removal of woody increasers (some trees and brush) where they have spread in parts of the prairie in the absence of historic bison and fire

- Re-vegetation, erosion control, water quality protection, and invasive species prevention will be a continual effort

- Planning for long-term (1,000+ years) sustainability and becoming a prairie sustainable model

- Maintain water quality amidst continued urban development. An intact native prairie filters and absorbs water, acting as a purifier for our watershed. Rock Creek remains pristine. Water quality is essential to people and wildlife.

- Explore the potential for expansion. The FWPP site can become a core anchor for potential expansion of a protection umbrella located in the heart of the last remaining large area of native Fort Worth Prairie. One key tool may be favorable tax value conservation easements on adjoining ranch lands as part of the Park and Preserve Complex.

- Active management to maintain high conservation value, including patch burns. Natural functions like large- scale bison migrations and fire are no longer present at the FWPP. Proper human management can mimic original natural forces and keep the Prairie pristine.

- Threats exist outside the Park of invasive species which could infect and degrade the Prairie.

- Explore and document climate change mitigation opportunities though carbon sequestration in protected and restored native prairies. The FWPP’s deep prairie roots store massive amounts of atmospheric carbon in the soil for thousands of years. The following quotes expand on these opportunities.

- “Recent models of land use suggest terrestrial systems can mitigate the increase of atmospheric CO2 by sequestering C into vegetation and soils … Carbon sequestered by soils occurs primarily through plants… Some of this carbon in the soil can persist in soils for hundreds and even thousands of years. … Much of the central U.S. and Canada, which was once prairie, is now in cultivated agriculture. The grasses of prairies store much of their carbon below ground, which is eventually converted to soil organic carbon.” (Testimony of Dr. Charles W. Price, Professor of Soil Microbiology, Kansas State University, “United States Senate Subcommittee on Production and Price Competiveness Hearing on Carbon Cycle Research and Agriculture’s Role in Reducing Climate Change”. 4 May 2000.)

- “Since the breaking of agricultural land in most regions, the carbon stocks have been depleted to such an extent, that they now represent a potential sink for CO2 removal from the atmosphere.” (J.J. Hutchinsona, C.A. Campbella and R.L. Desjardins, Science Direct, November 2006.)

- “Using prairie [restoration projects on already endangered land]… “even when grown on infertile soils” … “would lead to the long-term removal and storage of from 1.2 to 1.8 U.S. tons of carbon dioxide per acre per year.

This net removal of atmospheric carbon dioxide could continue for about 100 years, the researchers estimate.” (National Science Foundation report, 7 December 2006.)

2. Teaching

GPRC performs all of its Ecological Health education work for the public through its Plains Youth InterACTIONTM, Restoration Not IncarcerationTM, and Your Health OutdoorsTM programs. Plains Youth InterACTIONTM participants are youth who are either involved in direct leadership program/education opportunities (often in an intervention setting), or youth from schools or alterative community-based agencies who utilize the FWPP to supplement their learning and life/technical skills through Ecological Health practices and principles. Your Health OutdoorsTM participants are all age non-intervention members of the general public who support their own health through getting outdoors on the FWPP (and other GPRC Ecological Health locations, such as the Calisteo Basin Preserve in Santa Fe County, New Mexico) for hiking, service, bird watching, photography, and other respites.

In addition, the following teaching efforts are currently in progress or proposed:

- General public education and advocacy in support of conservation and Ecological Health, with a specific emphasis on grasslands, the world’s most endangered and least protected ecotype.

- Year-round school and youth day trips or volunteer work projects from North Texas and beyond. Several schools around the country are successfully using an ecology curriculum to teach their main STEM and other course work. For example, Manzo Elementary School in Tucson AZ “is moving towards developing a PACE- Grade 5 curriculum centered around reconciliation ecology, the science of inventing and establishing new habitats to conserve species diversity in places people occupy. Students are learning with hands on horticulture and reconciliation ecology. This has proven to be an excellent vehicle in promoting student discussions connected to restoring relationships, understanding the consequences of actions, and context for therapy as well as character building.”

- Teaching how to live sustainably with native ecosystems, water, wildlife, and human needs.

- Outdoor public experiential opportunities.

- The FWPP will be the “classroom” for ecological studies and research by high schools, universities, and organizations such as BRIT (Botanical Research Institute of Texas). The FWPP is a seed source for high- biodiversity restoration projects in the area. For example, its unique “Prairie Barrens” area helped provide the seed source for the living green roof of the new BRIT building, which is a LEED Gold-certified facility.

3. HEALING

The FWPP will be an innovative ‘quiet park’.

The FWPP will advances the medical value of wild nature. It is at the forefront of exciting new efforts to improve human health through personal participation in the protection of wild nature, especially trauma and illness recovery. Nature therapy research supports this convergence of social work and ecological restoration. Partners include university social workers, as well as students.

Restoration Not IncarcerationTM in particular is a “healing” modality here, where formerly incarcerated young adults, many of who are homeless, can qualify for transitional green job opportunities while learning, Tier I, Tier II, and Tier III of Ecological Health practices and principles, which provide stabilizing life an technical skills. Reconnecting with nature and the living ecosystems that give us all life, and doing so in a service manner, where the “body” helps health the Earth and vice versa, breaks a cycle of disregard and disrepair of both. Restoration Not Incarceration, and Plains Youth InterACTION are evidence-based programs that have used the FWPP to help people heal violence, illness, depression, despair, conflict, apathy and incarceration, through personal participation in the protection and recovery of wild nature. Wild nature, in turn, benefits by recovering from an onslaught of annihilating forces.

Ecological Health is for everybody. The nationally emerging Ecological Health movement, of which GPRC is a main founder, is defined as “the interdependent health of humans, animals and ecosystems.” Ecological Health programming is a relatively new but increasingly important area of medical study. The FWPP offers:

- Quiet prairie and creekside wildland trails for hiking, wellness, and mental and physical “rebooting”, as well as work-in-nature opportunities, for the general public

- Social work eco-therapy intervention for troubled young people

- Direct trauma, crisis and illness recovery, including for injured and/or PTSD suffering war veterans

- Re-entry work programming opportunities for temporarily or formerly incarcerated persons through a Restoration Not Incarceration Work Scholarship Fund

- Application of new fields of ecopsychology and ecopsychotherapy to mental and physiological health studies and applied clinical psychosocial work

- Nature-based work therapy

Research on the health benefits of interacting with wild nature has shown the following:

Combating Nature Deficit Disorder: Recent studies show that children who interact with nature develop better in all ways. They score higher on tests, they get sick less often, and their concentration, motor skills, self-discipline, coordination, balance and agility, reasoning and observational skills, social interaction, and ability to handle stress are all markedly greater. For the latest research and resources, visit Children and Nature. GPRC programs ensures that our youth not only interact with nature, but help lead the recovery of our prairie wilderness areas.

Physical Health from Nature: A 2013 review of outdoor vs. indoor activity in the New York Times found: “In virtually all of the studies, the volunteers reported enjoying the outside activity more and, on subsequent psychological tests, scored significantly higher on measures of vitality, enthusiasm, pleasure and self-esteem and lower on tension, depression and fatigue after they walked outside.”

“…[A]ccess to [the natural environment] can modify pathways through which a low socioeconomic position can lead to disease. …Health inequalities related to income deprivation in all-cause mortality and mortality from circulatory diseases were lower in populations living in the greenest areas.” (Mitchell, PhD, Popham, PhD., “Effect of Exposure to Natural Environment on Health Inequalities: an Observational Population Study,” The Lancet, 8 November 2008).

Mental Health from Nature: University of Michigan psychologist Michael Berman and colleagues completed a study that found “Interacting with nature shifts the mind to a more relaxed and passive mode, allowing the more analytical powers to restore themselves … the kind of attention we need to study for exams, make financial decisions, and so forth—the business of daily life”, and that this ability to focus and concentrate is depleted in the constant noise and overstimulation of modern urban life. (“In Our Nature”, Newsweek, February 2009.

Then I discovered the prairie, and a slow healing began.

~ S. R. Jones, (2000)

4. CAPITAL CAMPAIGN

Creating and completing the new Fort Worth Prairie Park and Rock Creek/Lake Benbrook Complex as an ecosystem reserve

County, State, Federal, corporation, private individual and foundation money will permanently protect this national treasure. Companies, foundations, private trusts and individuals concerned about protecting native wildlife, the natural environment, and offsetting their carbon footprint can directly do so by financially supporting the permanent protection of native prairie grassland and root-system carbon storage in the new FWPP, as well as building a 1,000-years+ legacy model of health for all people.

5. FACTS

- The Fort Worth Prairie is a unique ecosystem of tallgrass prairie, limestone seeps, shortgrass prairie barrens, creeks, and wetlands. It is a southern biome of the North American Tallgrass Prairie, and one of the rarest ecosystems in North America. It is classified as G1/G2, (G1 means critically imperiled, less than 6 known occurrences. G2 means imperiled, 6-20 known occurrences. G1/G2 means there is uncertainty over the status (Brian Rowe, Texas Master Naturalist, 2007.). Only several thousand acres of the once 1.3 million acre Fort Worth Prairie ecosystem exist today.

- The FWPP is a biodiversity hotspot with rare plant communities that include hundreds of different native plant species. The FWPP ecosystem is of exceptional high quality. Most uncultivated remaining native prairies are degraded by overgrazing and subsequent species loss, and are heavily impacted by invasive weeds and brush.

- The FWPP serves as natural flood control, ground water retention, and helps protect and clean the Trinity River, as well as clean the air. Rock Creek and two intermittent downslope streams run through the FWPP.

- The FWPP has historic and cultural significance. It was the meeting ground for numerous Prairie Tribes including indigenous Caddo and Wichita, and nomadic Comanche and Lipan Apache people. Escaped black slaves in the tumultuous 1850s often traveled through the wild prairie on a fugitive rush to freedom in Mexico. The FWPP original land grant from Juan Sequin dates back to a soldier who fought at San Jacinto in the Texas Revolution. A 300-year old native Texas Cedar Elm tree thrives on the property, next to an old wagon lane road to Johnson County. Ruins of an Anglo settler’s old stone house, cellar, and cistern from the 1850’s remain, along with burial grounds and a mysterious, hand built rock wall almost 3 miles long.

- Preserving Dark Skies is an important element of the FWPP. Nighttime prairie star parties will be open to the public.

Summary

The following quotes sum up the FWPP effort as a national epicenter of Ecological Health:

“For 50 years I have been on the battlefield and in the trenches fighting for civil rights, human rights, voting rights, housing and transportation rights to provide parity among all of God’s people, but what good is it if all those rights were enacted and a polluted environment destroys us with disease and death. The timing is perfect for science and religion to assume its rightful, ordained leadership position – confronting aggressively any and all fears which would seek to destroy a perfect gift to us – THE ENVIRONMENT.” The Rev. Dr. Gerald Durley, pastor of the historic Providence Baptist Church, Atlanta.

Native prairie is one of the most imperiled ecosystems in the world, with a conversion rate faster than that of the Amazon rainforest.” U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, September 2010

“There is today an enormous body of sophisticated research proving that unlike incarceration, which actually increases offender recidivism, properly designed and operated recidivism-reduction programs can significantly reduce offender recidivism.” Crime and Justice Institute, National Institute of Corrections, and National Center for State Courts, 30 August 2007.)

Appendix: Resources

International Community for Ecopsychology (ICE) — http://www.ecopsychology.org

Gatherings, e-journal of the International Community for Ecopsychology — http://www.ecopsychology.org/journal/ezine/gatherings.html

Texas Tech quotes about the Prairie — http://webpages.acs.ttu.edu/nmcintyr/prairie_quotes.html

Children & Nature Network — http://www.childrenandnature.org